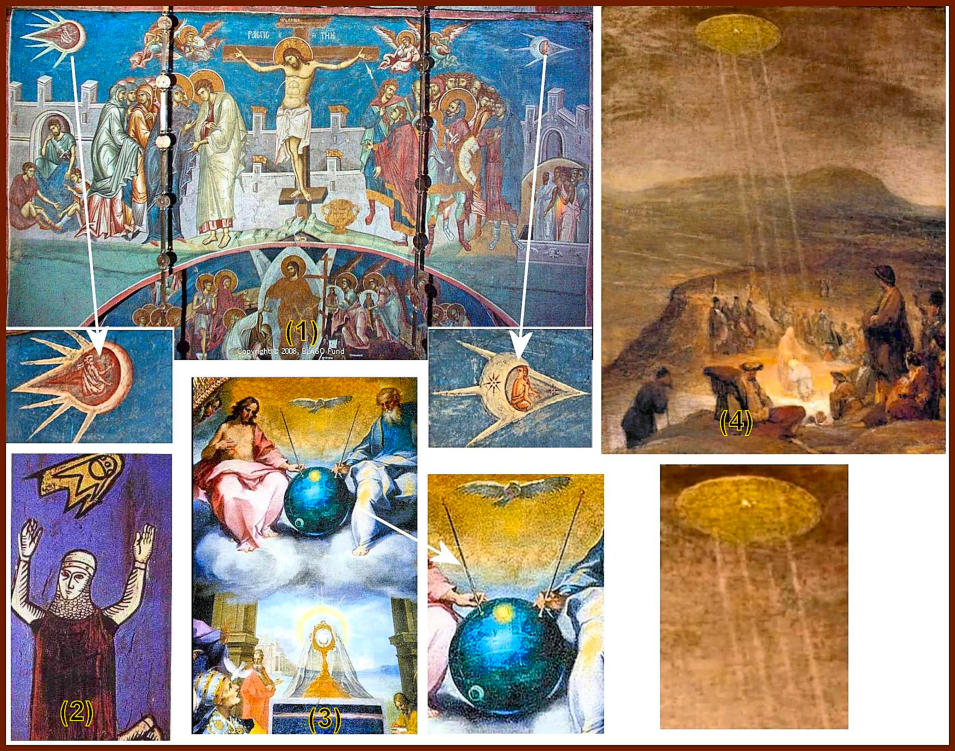

(1)

Fresco

“The

Crucifixion,”

circa

1350

A.D.

In

the

altar

of

Visoki

Decani

Monastery, Yugoslavia.

(2)

“Annales Laurissenses,” manuscript from the 12th century.

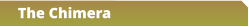

(3)

“The

Glorification

of

the

Eucharist”

by

Ventura

Salimbeni

(between

1568

and 1613) in Montalcino, Church of San Pietro.

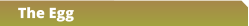

(4)

The

Baptism

of

Christ

(1710)

by

the

Flemish

painter

Arent

De

Gelder,

Cambridge

Museum

Fitzwilliam.

Here

we

refer

more

to

details

that

are

themselves fully figurative than to symbolism.

Sacred

scriptures

are

filled

with

references

to

lights,

angels,

doves,

stars,

and

other

signs

of

heavenly

origin.

All

this

has

led

painters,

especially

in

the

Middle

Ages,

to

depict

them

in

their

works,

though

sometimes,

as

we

see

in

this

sample,

there

are

interpretations

that

escape

symbolism

and

enter a fully figurative context.

(1)

“The

Crucifixion”

—

we

would

have

some

difficulty

interpreting

as

stars

what

is

described

here

as

flying

objects

with

figures

inside

and

with

an

attitude of manipulating something.

(2)

It

refers

to

an

event

in

the

year

776

during

a

Saxon

siege

at

the

castle

of

Sigiburg,

France,

which

could

be

defined

as

a

comet,

though

chronicles

mention

several

luminous

objects.

Four

centuries

later,

the

illustrator

drew

only one.

(3)

“The

Glorification

of

the

Eucharist,”

we

observe

the

Father

and

the

Son,

and

above

them

the

Holy

Spirit

represented

by

a

dove.

What

is

not

so

easy

for

us

to

interpret

is

the

sphere

they

hold

with

two

rods

like

antennae

and

the protrusion that projects from this sphere.

(4)

“The

Baptism

of

Christ,”

an

object

in

the

shape

of

a

disk

appears

shining

with

rays

of

light

on

John

the

Baptist

and

Jesus,

where

it

would

be

more

logical

to

have

painted

the

Holy

Spirit

in

the

form

of

a

dove,

as

other

artists

have

done,

based

on

the

belief

at

the

time

that

only

birds

had

been

seen flying.

RVM

THE SYMBOLISM IN THE PAINTING WORKS